|

Main Topics > Special and General Relativity > General Theory of Relativity

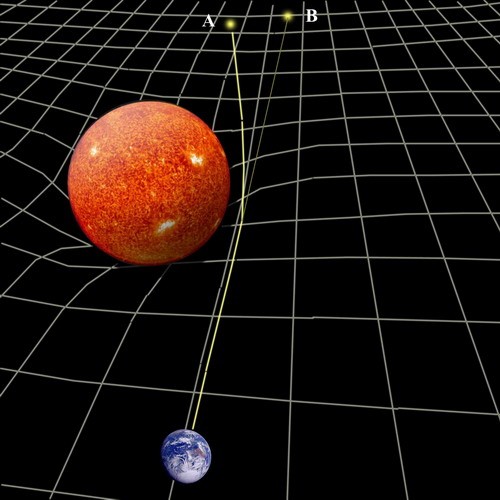

As we have seen, matter does not simply pull on other matter across empty space, as Newton had imagined. Rather matter distorts space-time and it is this distorted space-time that in turn affects other matter. Objects (including planets, like the Earth, for instance) fly freely under their own inertia through warped space-time, following curved paths because this is the shortest possible path (or geodesic) in warped space-time. This, in a nutshell, then, is the General Theory of Relativity, and its central premise is that the curvature of space-time is directly determined by the distribution of matter and energy contained within it. What complicates things, however, is that the distribution of matter and energy is in turn governed by the curvature of space, leading to a feedback loop and a lot of very complex mathematics. Thus, the presence of mass/energy determines the geometry of space, and the geometry of space determines the motion of mass/energy. In practice, in our everyday world, Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation is a perfectly good approximation. The curving of light was never actually predicted by Newton but, in combination with the idea from special relativity that all forms of energy (including light) have an effective mass, then it seems logical that, as light passes a massive body like the Sun, it too will feel the tug of gravity and be bent slightly from its course. Curiously, however, Einstein’s theory predicts that the path of light will be bent by twice as much as does Newton’s theory, due to a kind of positive feedback. The English astronomer Arthur Eddington confirmed Einstein’s predictions of the deflection of light from other stars by the Sun’s gravity using measurements taken in West Africa during an eclipse of the Sun in 1919, after which the General Theory of Relativity was generally accepted in the scientific community.

The theory has been proven remarkably accurate and robust in many different tests over the last century. The slightly elliptical orbit of planets is also explained by the theory but, even more remarkably, it also explains with great accuracy the fact that the elliptical orbits of planets are not exact repetitions but actually shift slightly with each revolution, tracing out a kind of rosette-like pattern. For instance, it correctly predicts the so-called precession of the perihelion of Mercury (that the planet Mercury traces out a complete rosette only once every 3 million years), something which Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation is not sophisticated enough to cope with. Gravity Probe B was launched into Earth orbit in 2004, specifically to test the space-time-bending effects predicted by General Relativity using ultra-sensitive gyroscopes. The final analysis of the results in 2011 confirms the predicted effects quite closely, with a tiny 0.28% margin of error for geodetic effects and a larger 19% margin of error for the much less pronounced frame-dragging effect. The General Theory of Relativity can actually be described using a very simple equation: R = GE (although Einstein's own formulation of his field equations are much more complex). Unfortunately, the variables in this simple equation are far from simple: R is a complicated mathematical object made up of 16 separate numbers in a matrix or "tensor" that describes the distortion of space-time; G is the gravitational constant; and E is another complicated number, also represented by a tensor, representing the energy of the object (or more accurately the 4-dimensional "energy momentum density"). Given that, though, what the equation says is simple enough: that what gravity really is is not a force but a distortion of space and time, and that the geometry of space and time depends not just on velocity (as the Special Theory of Relativity had indicated) but on the energy of an object. This makes sense when we consider that Newton had already shown that gravity depends on mass, and that Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity had shown that mass is equivalent to energy. Stephen Hawking and Roger Penrose’s singularity theorem of 1970 used the General Theory of Relativity to show that, just as any collapsing star must end in a singularity, the universe itself must have begun in a singularity like the Big Bang (providing that the universe does in fact contain at least as much matter as it appears to). The theorem also showed, though, that general relativity is an incomplete theory in that it cannot tell us exactly how the universe started off because it predicts that all physical theories (including itself) necessarily break down at a singularity like the Big Bang. The theory has also provided endless fodder for the science fiction industry, predicting the existence of sci-fi staples like black holes, wormholes, time travel, parallel universes, etc. Just as an example, the notionally faster-than-light “warp” speeds of Star Trek are based firmly on relativity: if the space-time behind a starship were in some way greatly expanded, and the space-time in front of it simultaneously contracted, the starship would find itself suddenly much closer to its destination, without the local space-time around the starship being affected in any relativistic way. Unfortunately, however, such a trick would require the harvesting of vast amounts of energy, way in excess of anything imaginable today.

|

Back to Top of Page

Introduction | Main Topics | Important Dates and Discoveries | Important Scientists | Cosmological Theories | The Universe By Numbers | Glossary of Terms | A few random facts | Blog | Gravitational Lensing Animation | Angular Momentum Calculator | Big Bang Timeline

NASA Apps - iOS | Android

The articles on this site are © 2009-.

If you quote this material please be courteous and provide a link.

Citations | Sources | Privacy Policy